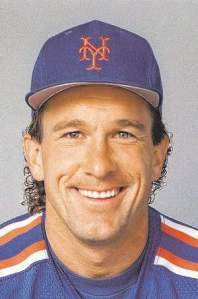

This photograph, which I first saw in the New York Times about twenty years ago, was my introduction to the Comedian Harmonists, one of the best vocal groups of the last century. Their history, as equally celebrated as their music, is a poignant story of lives interrupted and careers cut short by the Nazi regime.

Organized in Berlin in 1927, the Comedian Harmonists had a unique sound, though one quite reflective of Jazz Age music popular on both sides of the Atlantic. In descending vocal order, the group consisted of a high (lead) tenor, a second tenor, a swing vocalist who specialized in imitating musical instruments, a baritone and a bass. Mirroring the dance bands of that era, with their alto saxes wailing in the treble while a tuba or bass sax rumbled below, the Comedian Harmonists’ songs emphasized the same wide spectrum of sound. Their music featured leads sung by tenor Leschnikoff and bass Biberti, but the inner voices of second tenor Collin and baritone Cycowski were just as essential, if not more so, as were the arrangements by Frommerman, the group’s founder and faux instrumentalist, accompanied by Bootz at the piano.

Their repertoire covered a great deal of musical ground: traditional German folk songs, marches, novelty numbers about cactuses and crocodiles, classical pieces, operetta and popular tunes in at least four languages. My favorite songs are the contemporary numbers: the tango “Gitarren spielt auf,” “Wochenend und Sonnenschein” (“Happy Days Are Here Again”), “Du Armes Girl von Chor” (so very 20’s) and “In der Barzum Krokodil,” with a sly intro borrowed from the Nile Scene of Verdi’s “Aida.”

The Comedian Harmonists featured some wonderful arrangements, especially their version of “Stormy Weather” recorded in German (“Ohne Dich”) and French (“Quand il pleut”) with a lovely lead by second tenor Erich Collin. I’m also fond of their version of Cole Porter’s “Night and Day,” again in French (“Tout le jour, tout le nuit),” as well as the Italian “Ah Maria, Mari” with the soaring lead of Ari Leschnikoff, seconded by baritone Roman Cycowski, who stretches quite successfully into tenor territory. But if I had to pick an all-time Comedian Harmonists favorite, it would have to be “Der Onkel Bumba aus Kalumba tanzt nur Rumba,” perhaps their most intricate arrangement with its breakneck syncopation and bluesy ending. So much fun and a joy to hear.

While the Comedian Harmonists were a true product of Weimar Germany, they soon ran into difficulty when the Nazis came to power. Three of the singers were of Jewish origin, though Frommerman and Cycowski were not observant, and both sides of Collin’s family had converted long before his birth. Because the group was an international money-maker, it was allowed to continue, though with a dwindling performance and recording schedule. Things finally ended in 1935 when the Comedian Harmonists were banned outright, with the Jewish contingent temporarily relocating to Austria and later to Australia, restaffing and performing as the Comedy Harmonists. Although Biberti, Bootz and Leschnikoff regrouped with additional singers as the Meistersextett, issues with the Nazis continued. Their repertoire, the majority of which had been written by Jewish composers, was gutted; their remaining novelty numbers were later banned as too frivolous for the war effort.

The Comedian Harmonists never reunited as a group. Their post-war lives took divergent paths: for years Frommerman and Collin tried unsuccessfully to revive their musical careers, forming and reforming other vocal groups; Leschnikoff suffered one financial disaster after another; and Biberti became an antique dealer and master wood craftsman. Bootz remained a performing musician and club impresario, but Cycowski’s life took the most radical turn. Following his father’s murder at the hands of Polish Nazi sympathizers, he rededicated himself to his faith and became a cantor, active until his death at the age of 97.

Interviews with the then-surviving members of the group appear in Eberhard Fechner’s 1976 documentary “Sechs Lebensläufe” (“Six Life Stories”) which, sad to say, isn’t commercially available in a version with English subtitles. However, the entire film (actually a two-parter made for German television) is available on YouTube. Even if you don’t know a word of German, it’s worth watching the first several minutes just to see Leschnikoff and Cycowski react to hearing their old recording of “Gitarren spielt auf.” The tenor smilingly responds with “Schoen” (“Beautiful”), but it’s even more gratifying to watch Cycowski listen as his younger self sings. There’s a justified look of pride in his eyes as he nods his approval and echoes Leschnikoff’s appraisal: “Schoen.”

The Comedian Harmonists have been the subject of other films and books, including the 1997 feature “The Harmonists,” directed by Joseph Vilsmaier, which unfortunately suffers from Hollywooditis in its fictionalized story of the group. However, we finally have a comprehensive history in English by Douglas E. Friedman, “The Comedian Harmonists,” and there’s even a musical by Barry Manilow (“Harmony”) which has yet to make it to Broadway.

But there’s nothing like seeing the members of the group perform, and once again, YouTube comes through. There’s a truncated version of “Veronika, der Lenz ist da,” with Bootz grinning maniacally at the piano, and an intriguing clip from a 1936 Austrian film in which the Comedy Harmonists strut their stuff with musical instrument imitations. There’s no dearth of the group on CD, but I strongly recommend the remastered “History Records: Comedian Harmonists.” The sound is clear beyond belief, the artistry superb. This one shouldn’t be missed.