One of the documentaries I’ve enjoyed most in the last several years is “That Guy…Who Was in That Thing.” Featuring a roster of actors whose faces you’ve seen so many times, but whose names usually escape you, it’s 79 minutes of entertaining yet eye-opening anecdotes about life as a working actor, which as it turns out, is a rarity in Hollywood.

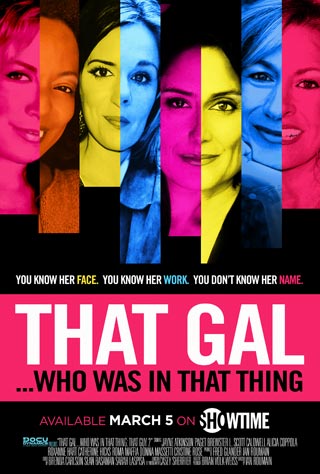

Now Ian Roumain, the director of that film, has produced a natural follow-up, “That Gal…Who Was in That Thing,” highlighting the trials and tribulations of the female version of the actor species (The majority of the participants in “That Gal” prefer to be described as “actors,” not “actresses,” so I’ll gladly follow their lead). The documentary is available on Showtime and On Demand, and it’s one you shouldn’t miss.

Despite their extensive resumes, the participants in “That Gal” were more obscure for me than the men in “That Guy.” The only face I could put a name to immediately belonged to Roma Maffia, only because of her appearances on the “Law & Order” shows and “E.R.,” both of which I watched regularly. Actor L. Scott Caldwell mentions early on that people tend to know her voice but not her name, and in fact, I wracked my brain until she finally mentioned playing Regina King’s mother in “Southland.” And while I knew Jayne Atkinson’s name from her extensive New York theater career, it was a big “So THAT’S who she is” when she appeared on-screen.

These are actors that luckily can make a living but aren’t stars. A couple, like Roxanne Hart, whose first film was “The Verdict” (she played the sister/guardian of Paul Newman’s comatose client) might have made that breakthrough when they were younger, but as luck would have it, it just didn’t happen. So now they keep on going with TV roles, winning a slot on a series if they’re lucky, and character parts in film, while at least two have branched out to other fields—in Ms. Hart’s case, directing in theater, and in Ms. Maffia’s, obtaining her master’s degree.

But what makes “That Gal” stand out from its male counterpart is an extensive and frank discussion of how Hollywood views and treats female actors. One of the documentary’s participants is Donna Massetti, a talent agent, who along with the actors who appear, details at length the problems of their early aging (at least in the eyes of producers), weight, appearance, etc., that are endemic in the industry. It’s the old story—a craggy 60 year-old male actor is “interesting,” a female actor that age will be sidelined into playing a great-grandmother. The bigger issue, though, is one of sheer numbers. There are always more roles for men because it’s a male-driven industry. The majority of the creative talent is still male, and the men get to present their vision. Fortunately with the emergence of cable TV and the development of original internet programming, the ladies are beginning to have their day.

However, some issues may never go away. Most of the actors in “That Gal” are mothers, and their stories about having to hide their pregnancies for fear of losing out on a role give you pause. L. Scott Caldwell’s account of what it cost her to send her son to live with his father while she gave a Tony-winning performance on Broadway is heartbreaking. And while Paget Brewster is exceptionally funny in describing how female actors are routinely assessed by men in the industry, she’s dead serious about being sexually assaulted while filming a bed scene.

The women who appear in “That Gal” are proud of their craft. After seeing it, I can only hope that they will have the opportunity to continue in their chosen profession for years to come.

P.S.: The title of this post comes from an amusing sequence in “That Gal” when the actors list the types of roles in which they’re routinely stuck with cast.