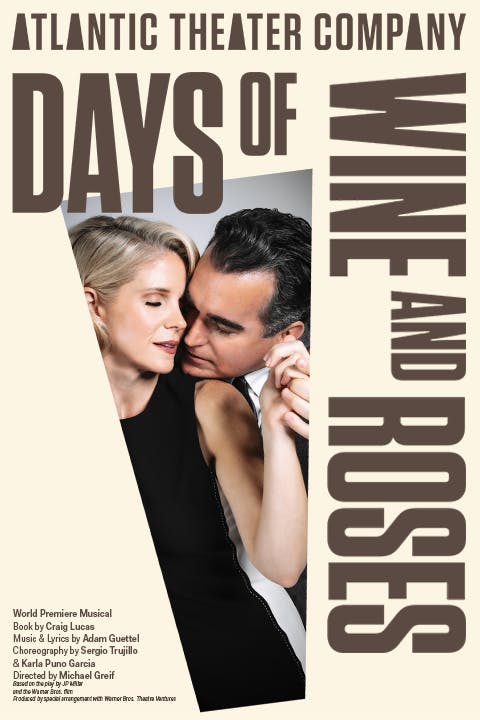

Sometimes the most unlikely stories are turned into musicals. At first blush, it would seem that “Days of Wine and Roses” could easily fit into that category, but judgment should be reserved in the case of the version now being presented by the Atlantic Theater Company in New York.

Written by J.P. Miller for television’s Playhouse 90 in 1958, the original version of “Days of Wine and Roses” starred Cliff Robertson and Piper Laurie as Joe Clay and Kirsten Arnesen. Better known of course is the 1962 film with Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick, giving what were among the best performances of their careers (In Jack Lemmon’s case, though, pride of place may go to his Jerry/Daphne in “Some Like It Hot”). Aside from length, the television and film versions differ in one significant respect—in the former, Joe and Kirsten are both drinkers when they meet; in the latter Kirsten is initially a teetotaler whose path to alcohol is paved by Joe. Both versions share the same tragic story—a young couple of promise devolving into what Joe ultimately calls “a couple of drunks afloat on a sea of booze and the boat sank.” While he eventually achieves sobriety by story’s end, Kirsten does not, though at least in the film we see her walk past a bar rather than entering it after Joe refuses to take her back unless she commits to staying sober.

Does this work as a musical? Based on the performance saw last Saturday, I’d have to say “sometimes.” In tone, this version of “Days and Wine and Roses” tends to follow the bleaker television play as opposed to the film, with some inventions such as a military backstory for Joe and a more prominent role for the couple’s daughter. But without a doubt, the show’s biggest asset is the pairing of Brian d’Arcy James and Kelli O’Hara as Joe and Kirsten. They’ve got chemistry, an essential component in making this story work, and it’s a pleasure to watch them perform.

However, the addition of song to this story does very little for the most part, and it’s not necessarily the fault of the show’s creators. A musical version of “Days of Wine and Roses” would have to overcome two major issues—the familiarity of the material and its dramatically powerful nature. Music can’t heighten what are already dramatic peaks—Joe’s cajoling Kirsten into drinking while she’s nursing, his attempted rescue of her from that seedy motel, and the crushing final scene, when Kirsten, unconfident of her ability to keep sober, flees Joe and their daughter. Nevertheless, there are stand-out moments in Adam Guettel’s score. The “Evanesce” duet with its Sondheim-like tonality and rhythm, while initially playful, takes on a darker hue later in the show when Joe and Kirsten no longer drink for enjoyment but to feed their addiction. Joe’s heartrending apology to Kirsten in song after he loudly arrives home drunk late at night, waking their baby, is another standout, as is Kirsten’s reprise of Joe’s “Forgiveness” song, when at last we hear Kelli O’Hara’s radiant soprano soar above the staff.

“Days of Wine and Roses” is currently playing through July 9. See it and decide for yourself.