One of Broadway’s most legendary flops, Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s 1981 show, “Merrily We Roll Along,” is enjoying a renaissance. I’ve written before about my love for this musical, and it was wonderful to finally see it live on stage last week after years of listening to cast albums of its phenomenal score.

The current Broadway production, now playing a limited run, is directed by Maria Friedman who did the honors ten years ago for the Menier Chocolate Factory in London (You can view a full performance of this, taped in 2013, on YouTube). Physically the two productions are very similar, but are incredibly different in tone–all because of casting. For want of a better word, the protagonists in the London version come across as more adult. There are some excellent performances here, especially from Frank (Mark Umbers), Charley (Damian Humbley, who has a terrific singing voice and looks like a young Nathan Lane) and Gussie (Josefina Gabrielle). But the Broadway version is sweeter, all due to the obvious affection the characters as well as the actors exhibit for each other. They appear younger than their London counterparts, even when on stage as their 40-ish selves; consequently it’s not difficult to imagine their idealistic start despite their later frayed friendship.

The musical is famously based on the Kaufman and Hart play of the same title, and to a certain extent shares its faults and kinks. The gimmick of course is that both versions are in essence played in reverse. The musical opens in then-present day 1976, and each succeeding scene moves further back in time until we see the three main characters as their younger selves viewing Sputnik from a rooftop in 1957. I think this set-up hurts the show in at least two instances. We’ve just been introduced to Charley when he goes off with “Franklin Shepard, Inc.” while being interviewed on TV with Frank by his side. While the song is a showcase of satire as well as Charley’s bitterness, we’ve yet to know the source of his hurt. It’s not until later that we learn Frank has virtually been running their collaboration for years, setting it aside when it suits him to pursue more lucrative work.

However, the most glaring example of the backwards chronology hurting the story is the opening of the second act. There we see Gussie va-va-vooming through “Good Thing Going,” Frank and Charley’s song that she insisted be co-opted for her show. It’s not until we hear Charley sing it in the next scene, at Joe and Gussie’s party, that we experience its sweetness and appreciate what a travesty Gussie made of it (aided and abetted by a satirically excessive orchestration which makes me laugh every time I hear it). As she sings it, the context is gone–there’s more than a little of Frank, Charlie and Mary’s friendship alluded to in the song. This of course is a Sondheim trademark: dual purpose lyrics. We hear it in Gussie’s rendition of the verse she performs to “Good Thing Going.” The “baby” and the “man I’m married to” clearly refer to Frank and Joe, respectively, as she contemplates her future with the former.

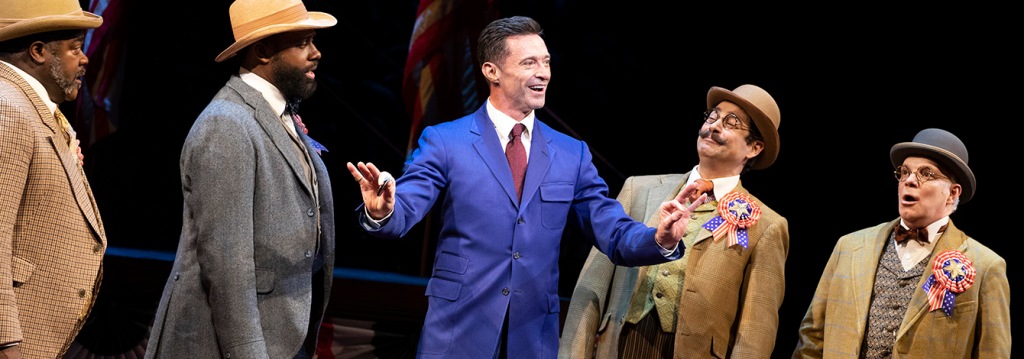

The three leads in the Broadway production are a treat to watch. Lindsay Mendez’s performance as Mary Flynn has Tony Award written all over it. You only wish the show gave her more opportunity to display her wonderful singing voice. Daniel Radcliffe makes a terrific Charley, performing the best version of “Franklin Shepard, Inc.” I’ve ever heard, and his rendition of “Good Thing Going” at the second act party scene is lovely. Jonathan Groff may come across as a bit too likeable while Frank is in narcissistic mode, but he de-ages very well as the show demands.

Just a few more notes:

Maria Friedman did a wonderful job with this show, but I have a couple of quibbles. I think Gussie is misdirected (and for the record, frequently inaudible), to the extent you wonder how Frank could have been taken in. And Beth’s version of “Not a Day Goes By” during the divorce court scene, with her acting like she should be in a straitjacket, is a bit much. Given the song and the fact that we’re hearing it for the first time, simple tearful regret would have been in order.

It sounds like the original Jonathan Tunick orchestrations have been kept. But what I miss from the original version of the score is the setting of the last chorus of “Our Time” in which the women top off the melody with a couple of bars of soprano descant in a particularly spine-tingling moment. While it’s performed that way in the 2013 version, its absence from the current production is a mystery since there are a number of excellent voices in the chorus, some of whom are readily identifiable as understudies for the leads.

I wonder about audience reaction, both present and future, to topical references of which “Merrily We Roll Along” contains more than a few. When I saw the show last week the audience laughed at the Irish jig music of “Bobby and Jackie and Jack,” as well as the number of Kennedys mentioned, but the then-current cultural references to Auden, Leontyne Price, Galina Vishnevskaya, etc., fell flat. Tellingly, when Frank and Charley audition for Joe, who illustrates his complaint about the lack of melody in their output by singing a few bars of “Some Enchanted Evening,”(Sondheim’s little dig), the audience just didn’t get it–I was the only one in my immediate vicinity who was laughing. Perhaps it doesn’t matter in the long run–Cole Porter was even more topical than Sondheim and his work remains very popular. However, EMI, which released a complete and excellent recording of Porter’s musical “Anything Goes” a number of years ago, made sure the audience got it by including a glossary of all of his topical references in the CD’s accompanying booklet. We may see more of this in the future.

Try to see “Merrily We Roll Along” if you can (And if you can get tickets!)