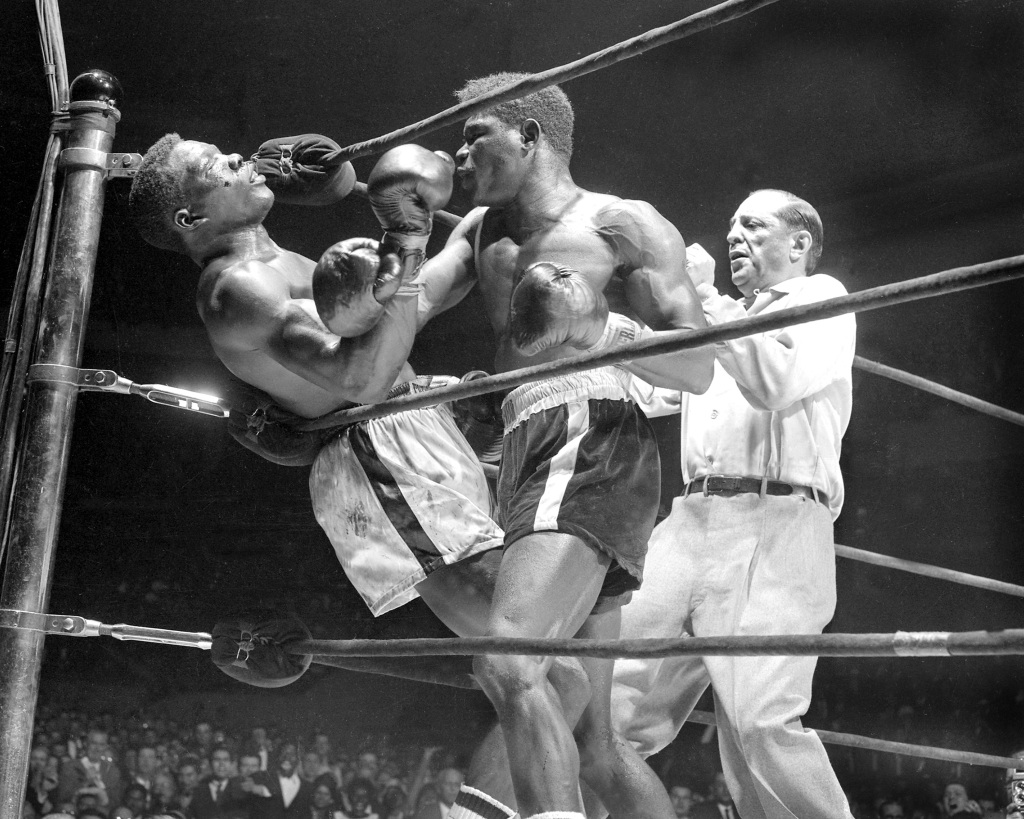

Certain images are guaranteed to stay with you your entire life. For me one of the most vivid is the photo you see above, which first appeared on the back page of a New York City tabloid on March 25, 1962. This was the conclusion of a nationally televised welterweight title fight between Benny “Kid” Paret (white trunks) and Emile Griffith (black trunks). Although Paret wound up in a coma and died ten days later, there’s no doubt this photo captured the man literally dying on his feet after seventeen unanswered punches from Griffith.

Emile Griffith’s life is now the subject of Terence Blanchard’s opera, “Champion,” currently enjoying a run at the Metropolitan Opera through May 13. At curtain’s rise we see an older Emile, sung by Eric Owens, suffering from dementia and haunted by Kid Paret’s death. The road to that fight and its aftermath are inextricably tied to who Emile Griffith was—a gay, closeted champ at a time when the love that dare not speak its name was deafeningly silent in sports. We flash back to Emile in his prime (Ryan Speedo Greene) who leads us through his history as a hat designer, singer and baseball player before he departs his native Virgin Islands for New York City where he turns to boxing.

“Champion” is an interesting amalgam of jazz, Caribbean rhythm, louche dive bar tunes and especially soaring vocal lines. This last is most evident in young Emile’s aria “What Makes a Man,” though for me the more striking aria belongs to Emile’s mother, wonderfully sung by Latonia Moore, which skirts atonality and seems to float in the ether as she describes her early life.

This production of “Champion” is particularly inventive, especially in its depiction of the Paret/Griffith bout (punches are thrown but freeze before landing). At the performance I attended the singers were uniformly excellent: Eric Owens was especially touching in depicting Emile’s dementia and his quest for absolution from Kid Paret’s son, Stephanie Blythe did an amusing, jazzy turn as the owner of a gay bar, and above all, Ryan Speedo Greene was extraordinary as both singer and actor, whether as an up-and-coming fighter or as the reigning champ, eventually forced to face retirement.

I can’t leave this discussion without mentioning the excellent documentary, “Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story,” which clearly demonstrates that Griffith’s furious beating of Paret after the latter had called him a “maricón” (“faggot”) at the weigh-in, was not the sole cause of Paret’s eventual death. Paret had lost his previous five fights and did not feel well prior to his bout with Griffith. Yet his unscrupulous manager wanted to squeeze the last possible dollar out of his prize money, the New York Boxing Commission should never have allowed Paret to get into the ring with Griffith, and the referee should have stopped the fight before he did, though whether this would have made any difference is something we’ll never know. “Champion” covers all of this, but unfortunately omits the words Benny Paret, Jr says to Emile when they finally meet in the most poignant scene in the film: “No hard feelings.”

“Champion” has already enjoyed a Live in HD showing (actually the performance I attended in-house). Watch for the repeat when it runs on PBS in the coming months.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

The Met recently presented an especially well-cast revival of its Robert Carsen production of “Der Rosenkavalier.” I first saw this when it premiered in 2017, and while I enjoyed the elimination of the powdered wigs in favor of a 1911 setting, I’ve got some reservations now. The cannons in von Faninal’s Vienna town house are a bit much, but over the top honors go instead to the third act set in a brothel (if memory serves the libretto calls for a “disreputable inn” for Ochs’ assignation with Mariandel). While Octavian’s selection of Mariandel’s “look” from a parade of prostitutes is amusing, the tawdriness becomes predictable, not to mention that Octavian and Sophie’s making out on a bed in view of von Faninal and the Marschallin is one big “Why?”

Fortunately the three female leads made the performance I attended just glow. Lise Davidsen, in her role debut as the Marschallin, surprised me with the sensitivity of her portrayal. Samantha Hankey was an excellent Octavian, both vocally and dramatically, and I’d very much like to see her more frequently at the Met in seasons to come. Erin Morley, who may be the best musician among opera singers today, was as always just perfect as Sophie. If I could have asked for more, I would have liked to have seen Matthew Polenzani’s egotistical Italian Singer again, as he autographs his latest record for the Marschallin with a supreme flourish.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Once of the best Saturday afternoon broadcasts from the Met came several weeks ago with “La Traviata.” Angel Blue made a fabulous Violetta, and the best part of the performance came in the second act, when she was partnered by Artur Rucinski’s Germont. What made this so refreshing was the sound of two artists with beautiful voices playing the scene with such attention to the emotional shifts of their characters’ confrontation, and (surprise!) adhering to the written dynamics of the score. If only more artists would follow their lead.