There are many operatic comedies, but if there’s a work that ends on a more joyous note than “Le Nozze di Figaro,” I’ve yet to see it. Indeed, Saturday’s finale to Mozart’s opera, courtesy of the Met’s Live in HD telecast, was cause for elation.

There’s just so much in “Figaro”: servant vs. master, long-lost parents, assignations in the garden, a randy pageboy who enjoys dressing as a girl, and most of all, that incredible Act Two, with its musically intricate and plot-twisting finale. Not to mention the funniest moment in opera—when Susanna, not Cherubino, steps out of the closet, to the Count’s complete stupification. (For the record my other favorites are Mistresses Ford and Page discovering Falstaff has sent them both the same love letter, the ménage à trois of “Le Comte D’Ory” and Almaviva and Rosina singing of how they’ll make their getaway instead of making their getaway while Figaro is “andiam”–ing them onward).

Richard Eyre’s production, which opened the current Met season, sets “Figaro” in 1930’s Spain. In my experience putting the singers in contemporary dress often frees them, not only from the literal constraints of corsets and powdered wigs, but from a type of formality that can be distancing. In short a modern dress production seems to enable them (and the audience) to relate to their characters and each other more easily than in a traditional staging. Such was the case here—the singers seemed to be enjoying themselves to the hilt.

There’s been a great deal of debate as to what that ’30’s setting signifies in view of Franco and the looming Civil War. I see it in a different light. Let me give you a hint: think Renoir’s “The Rules of the Game,” not politics. In fact if memory serves, Renoir precedes the action of his film with a quote from the source of the opera, Beaumarchais’ “Le marriage de Figaro.” Like the world of that film, the regime Eyre portrays is corrupt and dying; what’s left is love, the chase and other divertissements.

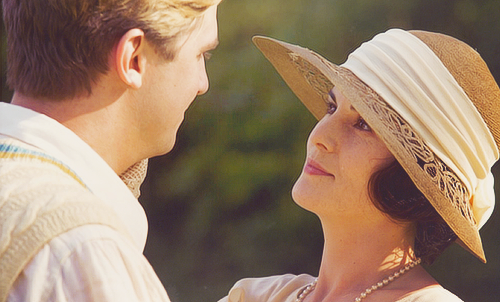

Eyre begins the production with a prequel that accompanies the overture. I didn’t care for his use of this device in his production of “Werther” last season, but I very much enjoyed it here. The scenes on the revolving set featured a maid running to work from the Count’s chambers while hastily dressing en route; the knowing looks of her fellow servants when she finally reports to her post; the gardener Antonio, already tippling in the a.m.; and the Countess, restlessly tossing in her bed—alone.

This was the 75th performance of “Le Nozze di Figaro” conducted by James Levine at the Met, and musical matters were as crisp as ever. The cast was excellent. Ildar Abdrazakov, shorn of his beard and Prince Igor’s long locks, is an engaging and enormously attractive Figaro. He and Marlis Petersen made an interesting team. Somewhat cast against type (she was a sinuous, dangerous Lulu at the Met several seasons ago), she proved a slightly older and definitely wiser Susanna than usual. Susanna is no ingenue, and variations on the role are most welcome. Years ago I saw Catherine Malfitano (pre-Salome and Tosca) perform a lovely, vulnerable Susanna, while Judith Blegen brought her sharp intelligence to the role. During the second act jousting with the Count, her expression wasn’t just “How did a nice girl like me end up in a mess like this?” it was “How did a nice smart girl like me” etc. In the current production the modern era works to Petersen’s advantage—she could have given Carole Lombard a run for her money in any 30’s screwball comedy.

I have to admit one of my main reasons for buying a ticket to this performance was to hear Peter Mattei sing “Contessa, perdono.” For sheer beauty of sound, there are few currently active baritones who can touch him. His Count Almaviva possessed the most important attribute necessary to putting the role across—authority, which he never lost despite the many times he was outfoxed by Figaro, Susanna and nearly everyone else on stage. I would have liked to have seen a Countess who could truly match him, but Amanda Majeski isn’t quite there yet, though she may well be in the future. I thought her performance a bit one-note—this Countess should have been on Prozac, though she eagerly joined in the many twists and turns of Act Two. I tend to think the overdone depression was more Eyre’s take on the character than hers, so there may be some tweaking in the future.

Isabel Leonard is a beautiful woman with a lovely voice, but I wasn’t really impressed until seeing her performance as Cherubino. She’s inside his skin, and looked quite dashing in that white suit. However, I was somewhat disappointed by “Voi che sapete.” She acted the lyrics to the aria, which resulted in some abruptly terminated phrases. But the aria is really a performance piece, and I would have preferred to have heard it as pure music rather than a vehicle by which Cherubino too obviously shows his befuddlement and anxiety to the Countess. Since it’s such a calling card for lyric mezzos, I can’t imagine this was Ms. Leonard’s idea, but it needs to be thrown overboard forthwith.

The rest of the cast was exemplary: Greg Fedderly’s Don Basilio seemed like Paul Lynde revisited, Susanne Mentzer, a former Cherubino of distinction, was a wonderfully arch Marcellina and John Del Carlo blustered becomingly as Bartolo. There was also a star in the making—Ying Fang, whose Barbarina had far more voice that you usually hear in this role. She’s got the limpid sound and the charm to be a wonderful Mimi, and I look forward to hearing more from her in the future.

What a lovely way to start a season of opera.

Some food for thought: Here’s a snapshot of what’s wrong with opera in America today. At my local multiplex there were only about 40 people in attendance for the “Figaro” HD telecast. I spotted one couple in their early 30’s, another in their 40’s, and a young woman in her 20’s who arrived with her mother. No one else in the theater would see 55 again, and in fact, the majority of attendees appeared to be in their late 60’s and far beyond. And, sad to say, the situation is no different at the university where I usually attend HD telecasts. So the marketing folks better get cracking pronto, before there’s no audience remaining to appreciate some of the greatest works ever created.